Messiah

Overview

Messianic Hebrew Canon

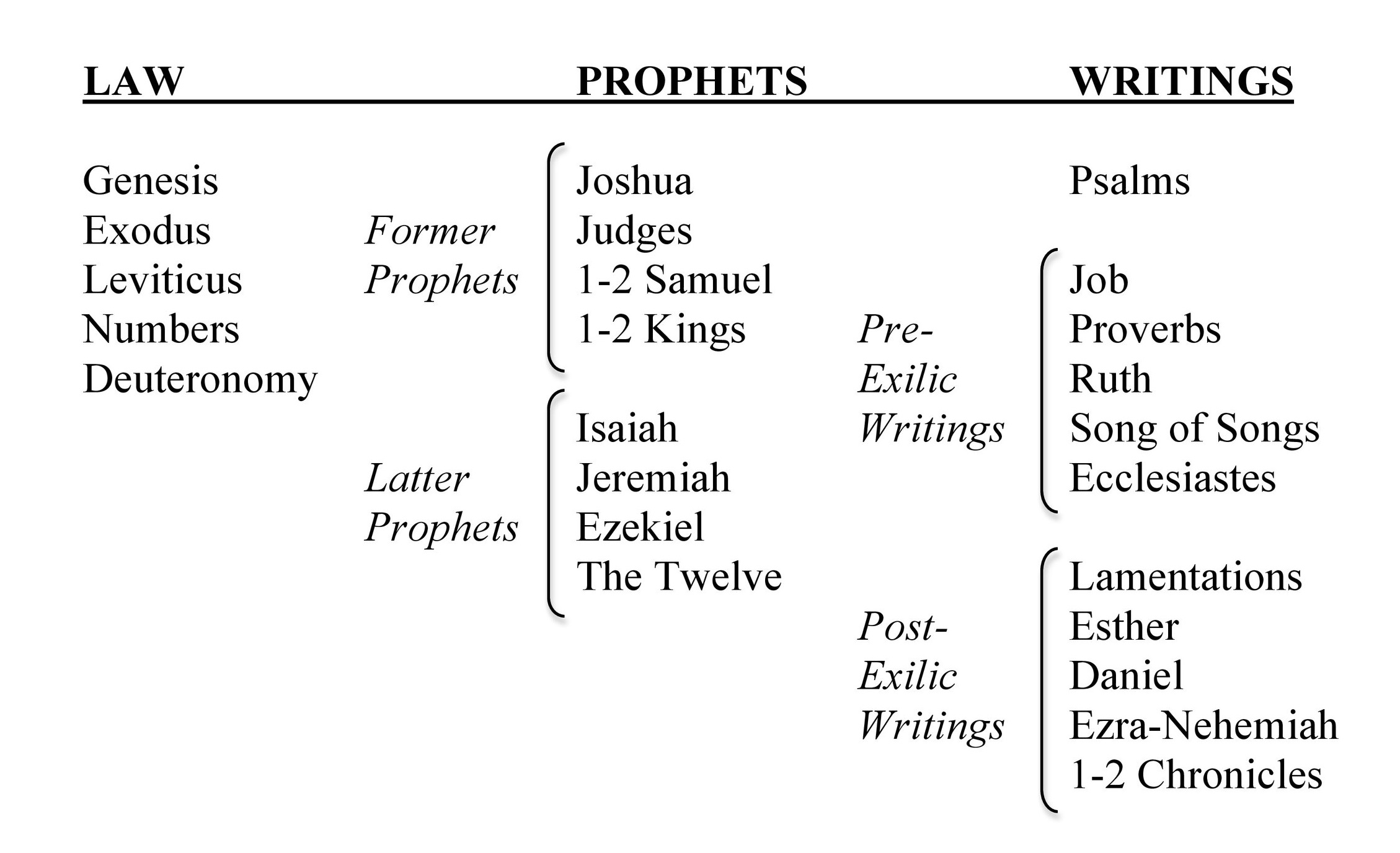

The Hebrew Bible, known as the Tanakh, is the sacred canon of Jewish Scripture. It is composed of three major divisions: Torah (Law), Nevi’im (Prophets), and Ketuvim (Writings). This tripartite structure forms a theological narrative that anticipates the arrival of the Messiah.

Diagram from: Why We Should Use the Hebrew Order of the Old Testament.

The Law

The Protoevangelium

The Tanakh opens with the foundational promise of redemption. Genesis 3:15, often called the Protoevangelium ("first gospel"), sets the trajectory for messianic expectation:

"I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your offspring and her offspring; he shall bruise your head, and you shall bruise his heel."

This promise establishes a conflict between two "seeds"—one representing the righteous line leading to the Messiah and the other embodying rebellion and opposition. The serpent will inflict a fatal wound on the Redeemer (bruising the heel), but yet the Redeemer will decisively defeat the serpent (crushing the head) through this. This pattern of victory through what appears to be defeat (down and then up) is developed throughout Scripture and is culminated in the cross.

The story of Cain and Abel (Genesis 4) immediately illustrates this battle, with Cain, the murderer, representing the serpent’s line, while Abel and later Seth (Genesis 4:25) continue the righteous lineage.

Eve’s exclamation at the birth of Cain in Genesis 4:1 is often translated as, “I have gotten a man with the help of the LORD.” However, if we take the direct object marker in a way that is consistent with its many occurences before and after in Genesis (and even in the same verse), it is more likely that Eve mistakenly believed that she had already given birth to the promised Messiah: "I have gotten a man, namely, the LORD." The expectation for a coming Redeemer was there from the beginning, yet God’s plan to bring about the Messiah would be carried out "in the fullness of time" (Galatians 4:4).

Victor P. Hamilton explains the translation, "Another problem concerns the word ʾeṯ that follows qānîṯî. This common term can be used in two ways: as the preposition 'with,' or as the marker of the direct object. Luther opted for the latter: 'I have received a man, namely (or even), the Lord'... Most modern commentators prefer the former option, rendering ʾeṯ as 'with the help of.' The question that needs to be raised here is whether this is a legitimate translation of ʾeṯ. Does the rest of the OT support such a translation?... We have translated ʾeṯ as from, which, we grant, is not a normal English value for the Hebrew word" (The Book of Genesis, Chapters 1–17, NICOT [Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1990], 221).

With this understanding of the messianic context, let us go back and consider Genesis 3:16. The ESV, recently updated, translates Genesis 3:16 as follows:

"To the woman he said, ‘I will surely multiply your pain in childbearing; in pain you shall bring forth children. Your desire shall be for your husband, and he shall rule over you.’”

The hebrew word for man (’îš) is here translated husband based on the assumed marriage context. However, the main focus at this point is the Messiah rather than marriage given the promise in the previous verse. This desire for the coming Messiah who would be born to the woman is more consistent with a messianic interpretation of Genesis 3:15 and 4:1. This translation of ’îš as man is supported in other verses:

Zechariah 6:12 – "Behold, the man (ha’îš) whose name is the Branch." Here, ’îš refers to the Messianic Branch, not an ordinary man.

Exodus 15:3 – "The LORD is a man (’îš) of war." YHWH is described as an ’îš in His role as a warrior.

Genesis 37:15 – "A man (’îš) found him wandering in the fields." Refers to an anonymous man, not a husband.

Judges 13:6 – "A man (’îš) of God came to me." Manoah’s wife describes the Angel of the LORD as ’îš.

It would thus be translated: "To the woman he said, ‘I will surely multiply your pain in childbearing; in pain you shall bring forth children. Your desire shall be for your man, and he shall rule over you.’”

This interpretation is also consistent with the expectation of the rule of the Messiah in Genesis. Genesis 49:10 says, "The scepter shall not depart from Judah, nor the ruler's staff from between his feet, until tribute comes to him; and to him shall be the obedience of the peoples." Eve knew that the Messiah would rule as king in the future, and she looked forward to that day as did the rest of God's people before the Christ came. Likewise, Numbers 24:17 says, "I see him, but not now; I behold him, but not near: a star shall come out of Jacob, and a scepter shall rise out of Israel."

The Prophet Like Moses

The Tanakh not only begins messianically but ends messianically too. Moses delivered Israel from Egypt, led them through the wilderness, and the covenant at Sinai is established with him. His life prefigures the coming Christ, who would deliver His people from sin through a greater Exodus and inaugurate a New Covenant by His blood.

Moses prophesied, "The LORD your God will raise up for you a prophet like me from among you, from your brothers—it is to him you shall listen" (Deuteronomy 18:15). At the end of the Torah (Deuteronomy 34:10-12), that expectation of a prophet like Moses is still future. Although Joshua is a type of the Christ in leading the people into the promised land, he is not the Christ.

The Prophets

Joshua a Type of Christ

The next section is the Prophets which is split into the former and latter prophets. It opens with Joshua being told, "This Book of the Law shall not depart from your mouth, but you shall meditate on it day and night, so that you may be careful to do according to all that is written in it" (Joshua 1:8). In Psalm 1:2 we are told that the "blessed man" delights in the LORD’s law and meditates on his Torah day and night. Psalms 1 and 2 form the introduction to the Psalter. By this connection, we see that the blessed man in Psalm 1 is also the Anointed one and Son of God in Psalm 2 who is the coming prophet like Moses.

Former Prophets Ending

The ending of the former prophets continues the pattern of messianic significance at the seams of the canon. The final chapter of 2 Kings (25:27-30) records the release of Jehoiachin (Jeconiah) from prison in Babylon, an event that may seem minor at first glance but holds deep theological significance. Jehoiachin, a descendant of David, had been taken into exile, seemingly marking the end of David’s dynasty. However, his release and elevation in the Babylonian court symbolize that the Davidic promise is not entirely lost. Even in exile, the Davidic line remains alive, hinting at a future restoration.

This passage ties into the broader messianic expectation by reinforcing the Davidic covenant (2 Samuel 7:12-16), where God promised David an everlasting dynasty. Despite Israel’s unfaithfulness leading to exile, the preservation of Jehoiachin’s line anticipates the fulfillment of this promise in a greater Davidic king.

The Latter Prophets

The Latter Prophets begin with Isaiah 1, which presents Israel’s spiritual corruption and impending judgment but also a glimmer of messianic hope. Isaiah 1:26-27 speaks of a future restoration where Zion will be redeemed with justice, foreshadowing the establishment of a righteous Davidic king (cf. Isaiah 9:6-7, 11:1-10).

There is hope of a future Davidic king who will bring justice and peace (Isaiah 2:1-4). Isaiah 7:14 foretells the birth of Immanuel, a child whose divine presence signifies God's faithfulness to His people. This theme expands in Isaiah 9:6-7, where the promised child is called "Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace", showing that the Davidic Messiah will also possess divine attributes. Isaiah 11 further develops this hope, portraying a spirit-filled ruler from Jesse’s line who will bring righteousness and extend Yahweh’s reign to the nations.

The Servant Songs (Isaiah 42, 49, 50, 52-53) introduce a new dimension to messianic expectation: the Messiah as a suffering, atoning figure. Isaiah 53 explicitly describes a Servant who will bear the sins of many, making Him the ultimate fulfillment of the sacrificial system. This suffering Servant is paradoxically exalted, showing that His humiliation leads to victory (Isaiah 52:13-15). The latter chapters of Isaiah (56-66) emphasize a new creation and an eschatological kingdom, where Zion is restored, and Yahweh reigns forever. Isaiah 61 is particularly significant, as it presents the Messiah’s mission: bringing good news to the poor, freeing captives, and proclaiming the year of the Lord’s favor, a passage Jesus applies to Himself in Luke 4:16-21.

The Twelve Minor Prophets, though often treated separately, function as a unified collection, tracing Israel’s decline, exile, and future hope through the coming of the Messiah. The book of Hosea sets the tone by presenting Israel as an unfaithful bride who will be redeemed by divine love (Hosea 1-3). Hosea 3:5 explicitly states that in the last days, Israel will return and seek Yahweh and David their king, reinforcing the expectation of a future Davidic ruler who will lead the people back to God.

Micah 5:2-4 provides one of the clearest messianic prophecies, foretelling that the ruler of Israel will come from Bethlehem but will have origins from eternity, a direct reference to Jesus’ divine and human nature. Zechariah expands on this vision, portraying a humble king riding on a donkey (Zechariah 9:9), a prophecy fulfilled in Jesus’ triumphal entry (Matthew 21:5). Zechariah also develops the priest-king theme, presenting the Messiah as one who will "sit and rule on his throne" and bear both kingly and priestly roles (Zechariah 6:12-13). This foreshadows Christ, the Melchizedekian priest-king (Hebrews 7). Zechariah 12:10 further predicts that the people of Israel will "look on him whom they have pierced," a prophecy directly linked to Jesus’ crucifixion (John 19:37).

The Twelve ends with Malachi, which closes the prophetic canon by anticipating the coming of the Lord and the forerunner Elijah (Malachi 3:1, 4:5-6). This passage is later applied to John the Baptist preparing the way for Christ (Matthew 11:10, Mark 1:2-3). Malachi's expectation of Yahweh coming to His temple finds fulfillment in Jesus, who, as Yahweh in the flesh, cleanses the temple and brings about the new covenant (Matthew 21:12-13, Hebrews 8). The Twelve collectively portray a messianic trajectory from Israel’s judgment to the hope of restoration, culminating in a divine Davidic ruler who will bring salvation to both Israel and the nations.

The Writings

The Psalms

The Writings begin with the Psalter. Although I've already touched on the Psalms some, there are more important details to look at to begin understanding the messianic import of the Psalms further.

A significant passage to understand for rightly interpreting the Psalms is 2 Samuel 23:1. The Masoretic Text (MT) traditionally translates נְאֻם דָּוִד בֶּן-יִשַׁי וּנְאֻם הַגֶּבֶר הֻקַּם עָל as “the oracle of David, the son of Jesse, the oracle of the man who was raised on high.” However, this translation depends on how one vocalizes הֻקַּם עָל. The Masoretes read it as "raised on high," but the Septuagint (LXX) and other early versions interpret it differently, reading it as “the man raised up concerning the anointed one” (anistēsas peri Christou). This means that David is not merely reflecting on his own exaltation but on his role in relation to the promised Messiah, the "anointed one" (מָשִׁיחַ / Christos).

This interpretation makes better sense contextually because David’s oracle immediately moves beyond himself to an eschatological figure, emphasizing a righteous ruler who will establish an everlasting kingdom (2 Samuel 23:3-5). David speaks of a just ruler who will rule in the fear of God and compares this figure to the rising sun bringing light to the earth (v.4). This imagery recalls messianic prophecies like Numbers 24:17 (“A star shall come out of Jacob”) and Malachi 4:2 (“The sun of righteousness shall rise with healing in its wings”).

Furthermore, the statement “it is not so with my house” (v.5) confirms that David is looking beyond his immediate dynasty (it is not written in the form of a question). Though his house has faced turmoil (e.g., Absalom’s rebellion), the Davidic covenant (2 Samuel 7) remains firm, and David acknowledges that the fulfillment of God’s promise is still future. This directly links 2 Samuel 23 to the expectation of the Psalms, which continually anticipate a coming king who will perfectly embody righteousness and divine rule (Psalm 2, 72, 110).

Reading 2 Samuel 23:1 as a reference to the Messiah provides a strong hermeneutical key to the Psalms. Many scholars have also begun to see the significance of Psalms 1 and 2 which are the "doors through which one enters into the house of praise."

Robert Cole explains, "As a compound introduction to the entire collection, the first two psalms announce the principle subject matter of the entire book: the triumphant monarch. The sequence of Psalms 20 to 24 continues the discussion of the monarch's suffering and subsequent deliverance" (Why Psalm 23 is Not About You, p. 18).

Part of the significance of this is seeing that the Psalms are primarily about the Messiah, the "blessed one" (1:1). He is blessed, and we can be likewise be blessed by virtue of taking "refuge in him" (2:12). It also means that we must take into account the structure and context of the Psalms. The macro-level structure of Books 1 through 5 is significant as well as connections between Psalms on a smaller level such as between Psalms 20 to 24.

Chronicles

The Writings end with 2 Chronicles 36:22-23. This passage is messianically significant because it leaves Israel’s story open-ended with an expectation of a future Davidic restoration, linking it to broader eschatological and messianic themes. Unlike 2 Kings, which ends on a note of exile and uncertainty, the Chronicler ends on a note of greater hope by recording Cyrus’s decree, which allows the Jewish exiles to return and rebuild the temple. This sets the stage for a greater fulfillment beyond the immediate post-exilic restoration:

“Thus says Cyrus king of Persia, ‘The Lord, the God of heaven, has given me all the kingdoms of the earth, and he has charged me to build him a house at Jerusalem, which is in Judah. Whoever is among you of all his people, may the Lord his God be with him. Let him go up’” (2 Chronicles 36:23).

The Chronicler’s history is distinct from that of Samuel-Kings because it retells Israel’s story with a stronger focus on the Davidic dynasty, the temple, and divine promises rather than just the political downfall of the monarchy. Ending Chronicles with the return to rebuild the temple subtly invites the reader to anticipate a greater son of David who will rebuild God’s kingdom permanently. This expectation aligns with messianic prophecies like Isaiah 9:6-7, 11:1-10, and Zechariah 6:12-13, which foresee a Davidic ruler who will reign righteously and establish the ultimate house of the Lord.

Resources

Videos

Anthony Rogers, Messianic Prophecy.

ONE FOR ISRAEL Ministry, The Case for Messiah - An Old Testament Defense of the New Testament Faith.

Mike Winger, How to Find Jesus in the Old Testament.

Books

The Messianic Hope: Is the Hebrew Bible Really Messianic? (NAC Studies in Bible & Theology Book 9) (2010) by Michael Rydelnik is a great introduction.

The Moody Handbook of Messianic Prophecy: Studies and Expositions of the Messiah in the Old Testament (2019) is a helpful and comprehensive book to reference.

James M. Hamilton Jr. looks at larger themes and types of Christ in the Old Testament in Typology-Understanding the Bible's Promise-Shaped Patterns: How Old Testament Expectations are Fulfilled in Christ (2022).